Balancing protection of the old with the challenges of growth

By the 1990s Brisbane’s inner northern suburbs were subject to state-sponsored master planning and urban renewal programs, and all the inner city suburbs were a target for infill development, to increase their residential density.

Performance based planning and regional plans

At this time, a new planning act represented a significant change to the administration of planning policy in Queensland.

The Integrated Planning Act 1997 introduced 'performance based' planning - a hybrid of the discretionary planning seen in places like the United Kingdom and the code-based planning seen in the United States. It seeks to balance predictability with creative discretion, but has not been without its criticism.

The Integrated Planning Act 1997 created a framework of regional planning and infrastructure charging (charging developers a fee to provide utilities and other infrastructure for new development), which has been retained under the subsequent Sustainable Planning Act 2009 and currently in-force Planning Act 2016.

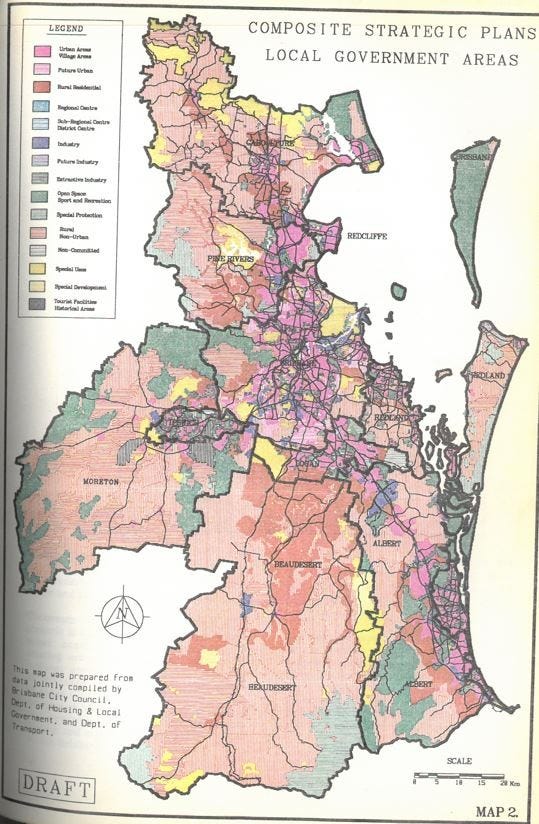

The early 2000s also saw the need to plan the South East as a region. The 200-kilometre city was sprawling, and the distinction between Brisbane and the Sunshine Coast to the north, the Gold Coast to the south and Ipswich to the west was being filled with more housing.

This meant the implementation of the SEQ Regional Plan. It's also had a few iterations (2005, 2009 and 2017) and the Queensland Government committed in 2022 to review it again. The 2017 plan modelling says that Brisbane needs an additional 18,000 dwellings per year.

The SEQ Regional Plan set 'consolidation' targets. For Brisbane, the State set a target of 94% of new dwellings to be sourced from the existing urban area Implementation on the ground, however, was left to Brisbane City Council.

Brisbane City Council plans for infill

Brisbane City Council’s planning scheme has had two major revisions since the introduction of performance-based planning – in 2000 and 2014.

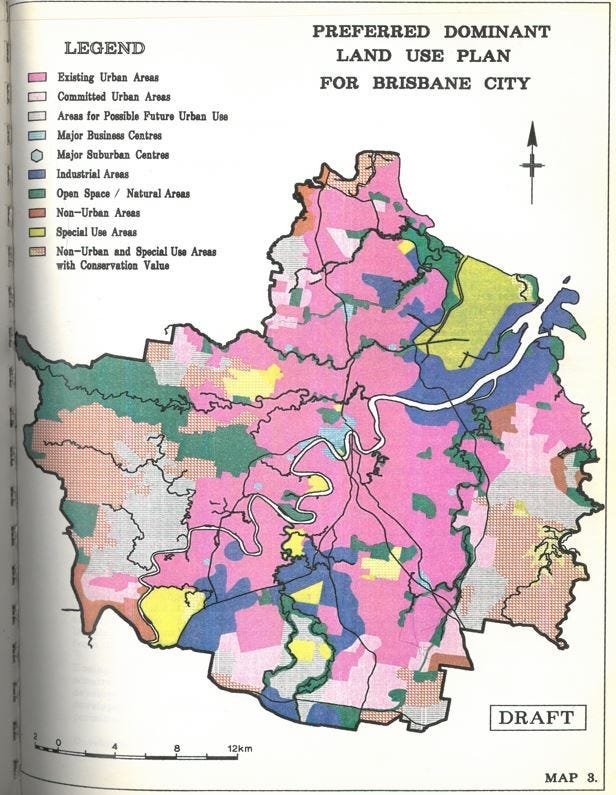

The 2000 scheme designated suburban centres which were rezoned for higher density and mixed use development, but the plan aimed to “encourage and support” the existing city centre as Brisbane’s major commercial centre (Courier Mail, 26 February 1999).

The plan continued the relocation of industrial areas away from the inner city, which had begun in earnest in the late 1980s, with a long-term plan to promote industrial use in Archerfield through to Wacol, and the Brisbane Port (Courier Mail, 26 February 1999).

Inner city suburbs were targeted for densification. For example, in 2005, amendments to South Brisbane’s local plan capped building heights between 7 and 10 storeys (Southern News, 15 December 2005) but these were removed following a change in council administration, and a 2010 amendment allowed buildings ranging from 15 to 30 storeys, depending on the location.

At the same time, Brisbane City Council introduced requirements to retain houses constructed prior to World War Two.

Character protections

In 1995 Brisbane City Council introduced a requirement for a development approval to remove or demolish character homes in suburbs constructed prior to 1947. These are the tin and timber homes often referred to as "Queenslanders" or "worker's cottages".

This was further refined in the City Plan 2000 where character residential areas were declared “demolition control precincts”, requiring an advertised planning application to remove or demolish a character house (Courier Mail, 20 April 2002).

When Campbell Newman (Liberal National Party) was elected Lord Mayor in 2004, he committed to introducing a neighbourhood planning system which could potentially expand protections to any local architecture of “community importance”, beyond pre-1947 houses.

Bipartisan changes were introduced incrementally between 2005 and 2008 to protect character houses from demolition or removal, which had only previously been protected if they were in groups of three (Courier Mail, 4 May 2005; Courier Mail, 14 February 2007).

In 2006, minimum lot sizes in demolition control precincts were increased from 400m2 to 450m2 to further prevent lot subdivisions (Courier Mail, 22 November 2006). The Deputy Mayor, David Hinchliffe (Australian Labor Party), also made clear his view that regulations on renovating character houses should be eased, but demolition controls tightened (Westside News, 14 February 2007).

As a result, a two bedroom, pre-1947 house could be renovated and extended, but could not be demolished. These provisions continue to apply today.

The 2014 planning scheme included greater emphasis on infill development and simplified the provisions to allow owners to shift character houses to one side and subdivide the lot.

The Character Residential (Infill) zone allows infill of a similar scale to the character house.

Character residential zones initially applied to inner suburbs but now extend to pre-war neighbourhoods across the city.

There are numerous examples of residents advocating for character protections when council proposes to rezone their properties for medium density (here, here, here - and so many more...).

Examples of local politics and their influence on planning decisions are numerous in Brisbane and outline the city’s difficult task of balancing growth with preventing urban sprawl.

Council bans townhouses

Brisbane City Council undertook community consultation which resulted in the Brisbane Future Blueprint in 2018. A direct result of this consultation was an amendment to the planning scheme that banned townhouses, rowhouses and small-scale apartments from the city's low density areas in 2020.

Low density zones over about 70% of Brisbane's residential land mass and this amendment prevented housing diversification across the majority of these suburbs.

Future challenges

The challenges are significant for Brisbane - but there are also significant opportunities. There's much to love about this city. It has a distinct urbanism that differentiates it from other places in Australia, and the world.

Here concludes my series of Planning Brisbane!