Green belts, failed plans and a "shocking" example of town development

In Part 2 we discuss how past planning decisions arguably paved the way (literally and figuratively) to path dependent urban sprawl, as well as the foresight of a few legislators that knew this wasn't going to be a good idea.

The Undue Subdivision of Land Act 1885 (Qld), which banned terraced housing and set minimum lot sizes, was repealed in 1923 with the passing of the Local Authorities Acts Amendment Act 1923 (Qld). The new legislation provided local authorities with the power to specify the maximum number of houses per acre in a future subdivision of land.

Path dependency of minimum lot sizes

The restrictions contained in the Undue Subdivision of Land Act 1885 (Qld) were, however, explicitly retained, including the minimum lot size of 16 perches per house.

Minimum widths were set for roads, with principal roads (for through traffic) set at 80 feet (24.4 metres), and the widths contained in the Undue Subdivision of Land Act 1885 (Qld) (66 feet for roads and 22 feet for lanes) were retained for secondary and residential roads and lanes, respectively.

A time before property developers and lobby groups

The government’s position at the time was to ensure local governments were not burdened with unnecessary maintenance expenditure for their road networks, as “wide roads are essential in their proper place, but where they are not essential, they are uneconomical, and the wider the unnecessary road the more uneconomical it is.” (Hansard, F.T. Brennan 7 August 1923, Queensland Parliament, p. 395).

In his Second Reading speech the Minister responsible for the legislation, Frank Brennan, spoke about profiteering by real estate speculators, stating that, due to the profits being made, “they cannot complain the person who is subdividing land is not in a position to pay a little more for the preparation of proper plans or for doing certain work before…the land is put on the market for sale.”

The Local Authorities Acts Amendment Act 1923 (Qld) provided local authorities more control over subdivisions, including requiring surveys, to enable purchasers to envision the future layout of the subdivision.

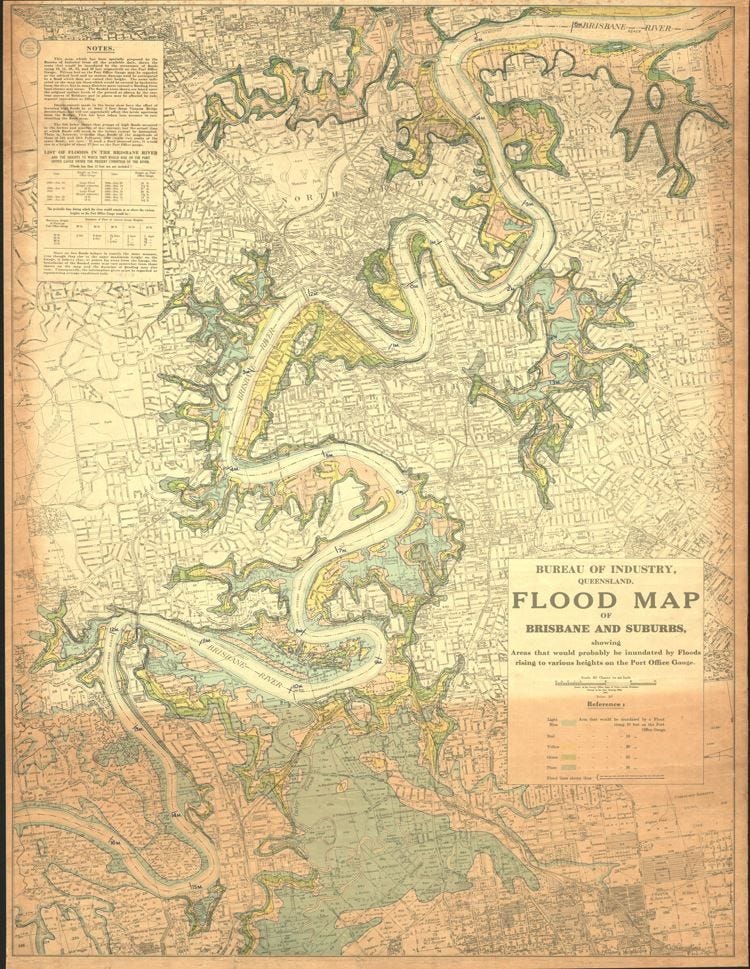

Moreover, with regards to parcel sizes, the Minister stated that “some of the matters which must be considered are the size and shape of each separate parcel, length of road frontage, situation of each parcel in relation to public convenience, means of access, whether the land is low-lying and incapable of being drained or unfit for residential purposes and the provision made for public garden and recreation spaces.”

Additional powers were granted to local authorities to make by-laws to fix the minimum areas and frontages for buildings.

Brisbane continued to grow and, by 1925, the amalgamation of 21 shires and councils meant Brisbane was the largest city administration area in the southern hemisphere.

Town planning trends influence Brisbane (kind of)

The unified local government gave Brisbane a significant opportunity for largescale planning, when compared to Melbourne and Sydney who continue to have multiple local governments within their respective metropolitan areas. Brisbane became the first city in Australia to appoint a city planner and create a town planning department, in 1925.

Nevertheless, despite powers to prepare planning schemes being granted in 1926 (Qld. Government Gazette, 1926, Vol, CXXVI pp 1069-1070, 20 March 1926), a planning scheme was not gazetted for the city until 1965, due to numerous obstacles.

The first town planning ordinances were gazetted in 1926, fixing a minimum lot size of 24 perches (607m2) and requiring developers to gain council permission before clearing trees.

A civic survey was conducted in 1928 in preparation for the drafting of a zoning plan, following international trend, particularly the proliferation of zoning in the United States.

The draft zoning plan divided the city into residential, industrial, and agricultural zones, and set side special areas for noxious industries, but was rejected by the state government for failing to provide adequate compensation to affected landowners.

"A very shocking example" of town development

In 1934, Brisbane was declared “a very shocking example” of town development, with little to done to zone, remove ‘noxious’ trade, plan suburbs, or improve transport (Qld, Pari. Deb., 1934, Vol. CLXVI, p. 890, 23 Oct).

This same year the Queensland Government enacted the City of Mackay and other Town Planning Schemes Approval Act 1934 (Qld) which set minimum requirements for the creation of local government planning schemes across the state.

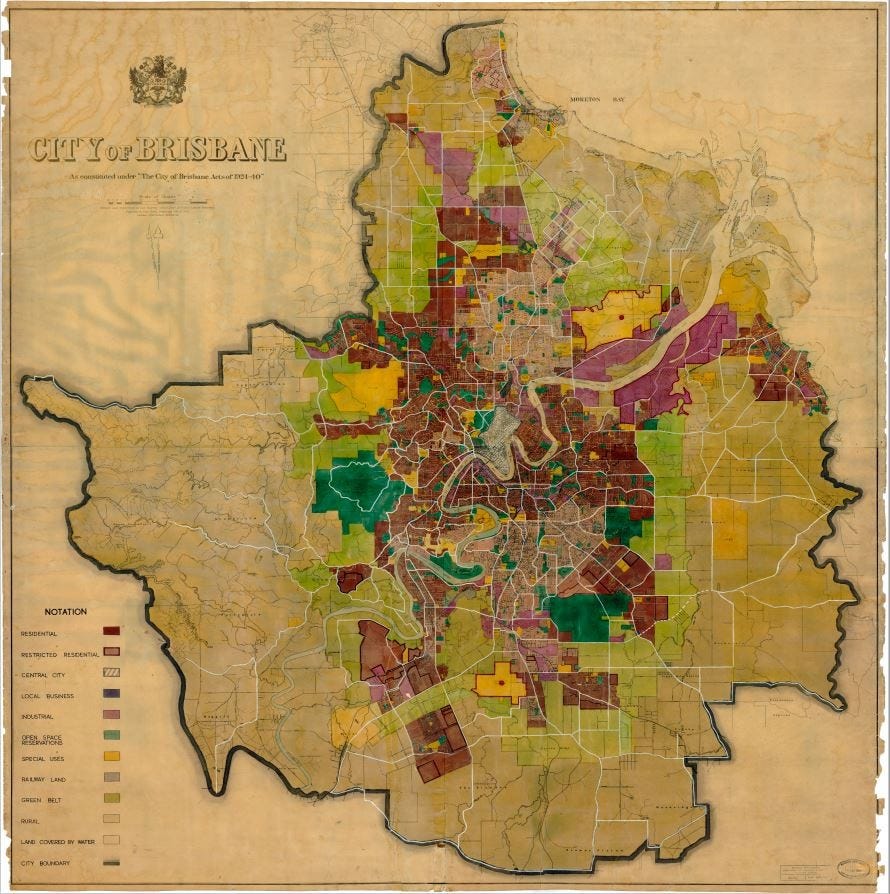

A 1944 zoning scheme was adopted by Council for the “orderly development of the city, while preserving its natural beauty” by “preventing ribbon development”, which referred to development along key road corridors (Courier Mail, 12 February 1944, p. 3).

The draft scheme divided the city into nine zones (three types of residential, three types of industrial, two types of business and a rural zone) and each zone was characterised by what land uses were permitted, which required approval including advertisement for objections, and which were prohibited.

Interestingly, the plan also included a mile-wide, encircling green belt of farms, open space, and parks to separate urban and rural uses.

Compact growth, public transport and public green space

The green belt included Toohey Forest and Mount Coot-tha, but also the contemporary suburbs like Carindale, Wishart, Parkinson, Algester and Forest Lake. Note the suburb of Inala, isolated beyond the green belt in the image below. A separate issue, but gives an indication of government approaches to social housing.

It was estimated that 500,000 people would reside inside the green belt and that private land within the green belt would be gradually acquired by council and held in perpetuity (Courier Mail, 12 February 1944, p. 3).

The green belt was modelled from other overseas jurisdictions, notably London, and the purported benefits included allowing for the “improved planning of passenger transport facilities.” (Brisbane Telegraph, 8 August 1950, p. 21).

It's important to recognise that this policy approach occurred at a time when other cities were retrofitting for increased private vehicle traffic. A stark difference arose between cities that remained compact, and those that planned around the proliferation of the car, allowing the urban area to expand exponentially.

The Lord Mayor stated that the object of the green belt was to prevent a sprawling city extending for “miles away from its centre” but added that he never hoped “…to see Brisbane proper holding a population of a million people.” (The Courier Mail, 23 April 1948, p. 3).

At the time, the future suburb of Acacia Ridge (13 kilometres from Brisbane's city centre) was considered “completely isolated”, with the Lord Mayor stating that “the cost of supplying services to it would be enormous” (Brisbane Telegraph, 18 April 1950, p. 7).

The green belt is abandoned

While adopted by Council, the 1944 scheme was not forwarded to the State Government as required by law. The Council nevertheless used the zoning proposal as a guide for granting approvals. In 1952 the Council attempted to have the zoning scheme ratified.

The version of the scheme presented to the Queensland Government in 1952 differed significantly from its 1944 version, as the Council had periodically amended the scheme on its own accord through resolutions of Council between 1947 and 1952, which technically had no legal effect.

The Minister ultimately refused to approve the planning scheme, noting a lack of up-to-date data, as the Council had not undertaken a civic survey, as well as a failure to provide sufficient commercial and industrial zoned land. A civic survey was later compiled in 1950-1951.

The green belt was based on ideas imported from the United Kingdom and, while they were accepted by professional planners, it was not accepted by the wider public (Minnery 2004). Reviewing the proposed planning scheme in 1954, the Director of Local Government emphasised that agricultural uses should be protected but questioned the utility of the green belt, noting that the low-density conditions of Brisbane did not fully justify the expense of a mix of public and private land being restricted from development (Cox 1968).

The green belt was abandoned in subsequent versions of the planning scheme, citing no justification, as well as public pressure that the proposal would “strangle the development of Brisbane and lead to congestion and slum areas.” (Courier Mail, 26 February 1949, p. 3).

The association between higher density housing and 'slums' is still as pervasive today as it was in the post-war period, and these decisions were to set Brisbane on the path of sprawl and car dependence.