Informal settlements and Australia's history of repeated housing crises

Lessons from Brisbane, Australia

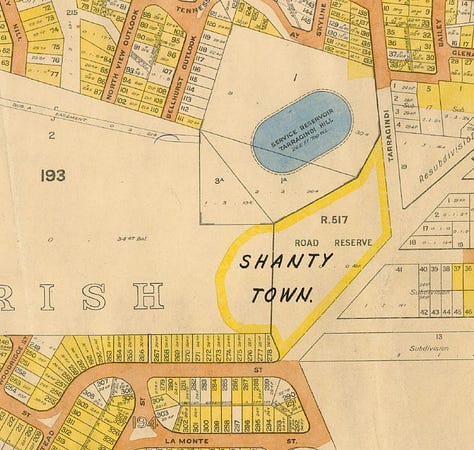

There are two motivations for this, my first official, Substack. Firstly, I came across a 1951 survey map while undertaking my PhD. In neat writing ‘shanty town’ is marked on the map - where I know a Brisbane City Council park and water reservoir exists. Secondly, while searching my family in Trove, I discovered a newspaper article about my great-grandmother having to evict someone from her house in 1947. These were both new facts to me.

The WW2 housing crisis

Like many Australian families, my family was impacted by the post-war housing crisis. In 1947 my great-grandmother was living in a corrugated iron shed, with her four kids (my grandfather included). She was about to have another baby, camping in Goulburn with no running water or electricity.

This situation was a result of a housing supply crisis. My Nanny had been living in Cowra after her husband was posted there during the war. They bought the house after moving back to Goulburn, but the woman living there - a single mum of 8 kids - refused to vacate. She had nowhere else to go. An eviction order was obtained.

But what happened to the Larkham family? Did they go onto homeownership during the post-war housing construction boom, like my grandad and his siblings? Or did they face more housing insecurity?

Fast-forward to 2024, and we have seen the re-emergence of shanty towns and camps in urban parks around the world.

Brisbane’s shanty towns

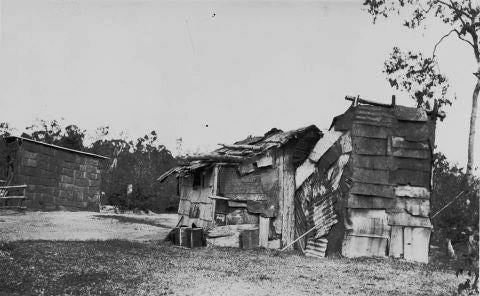

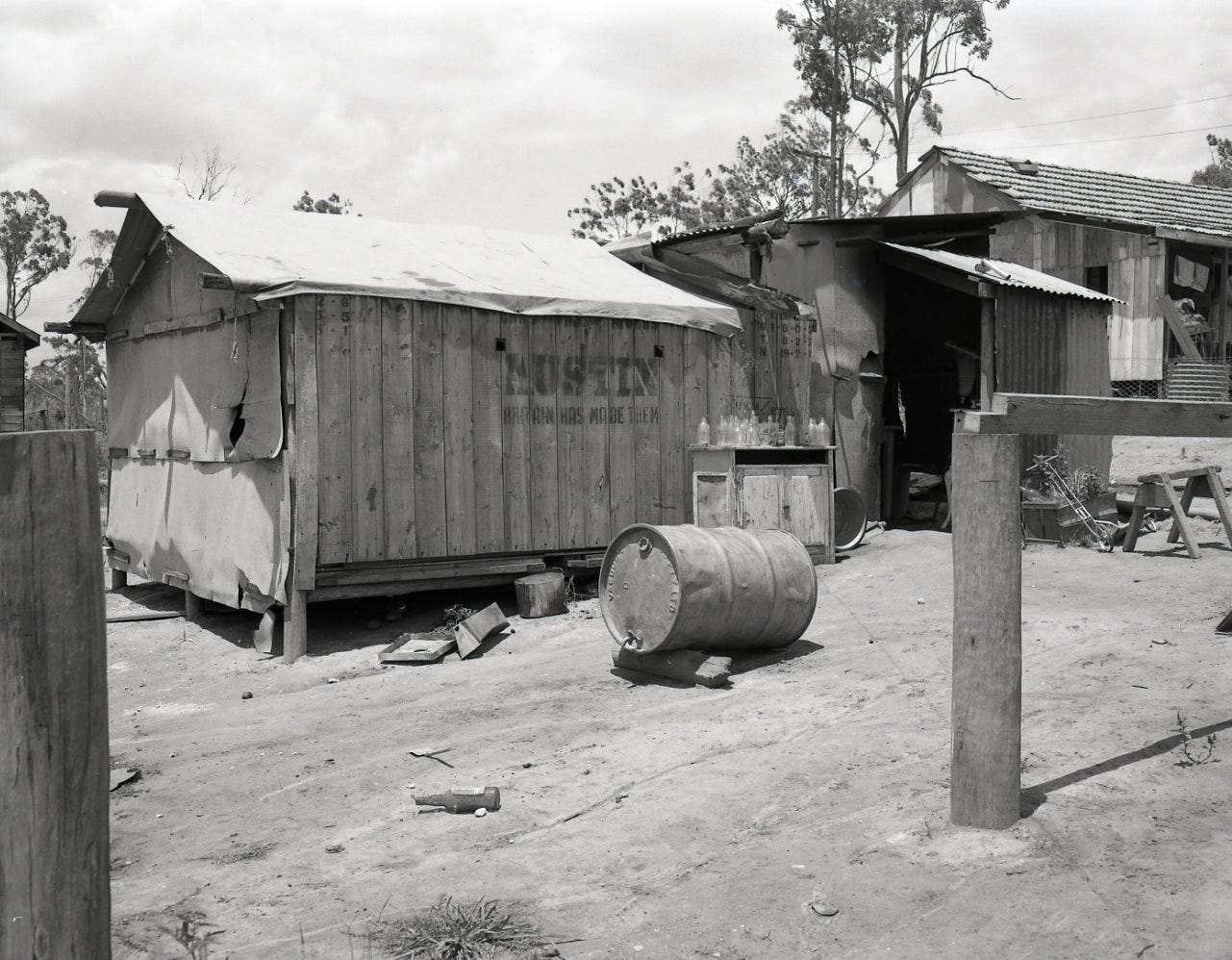

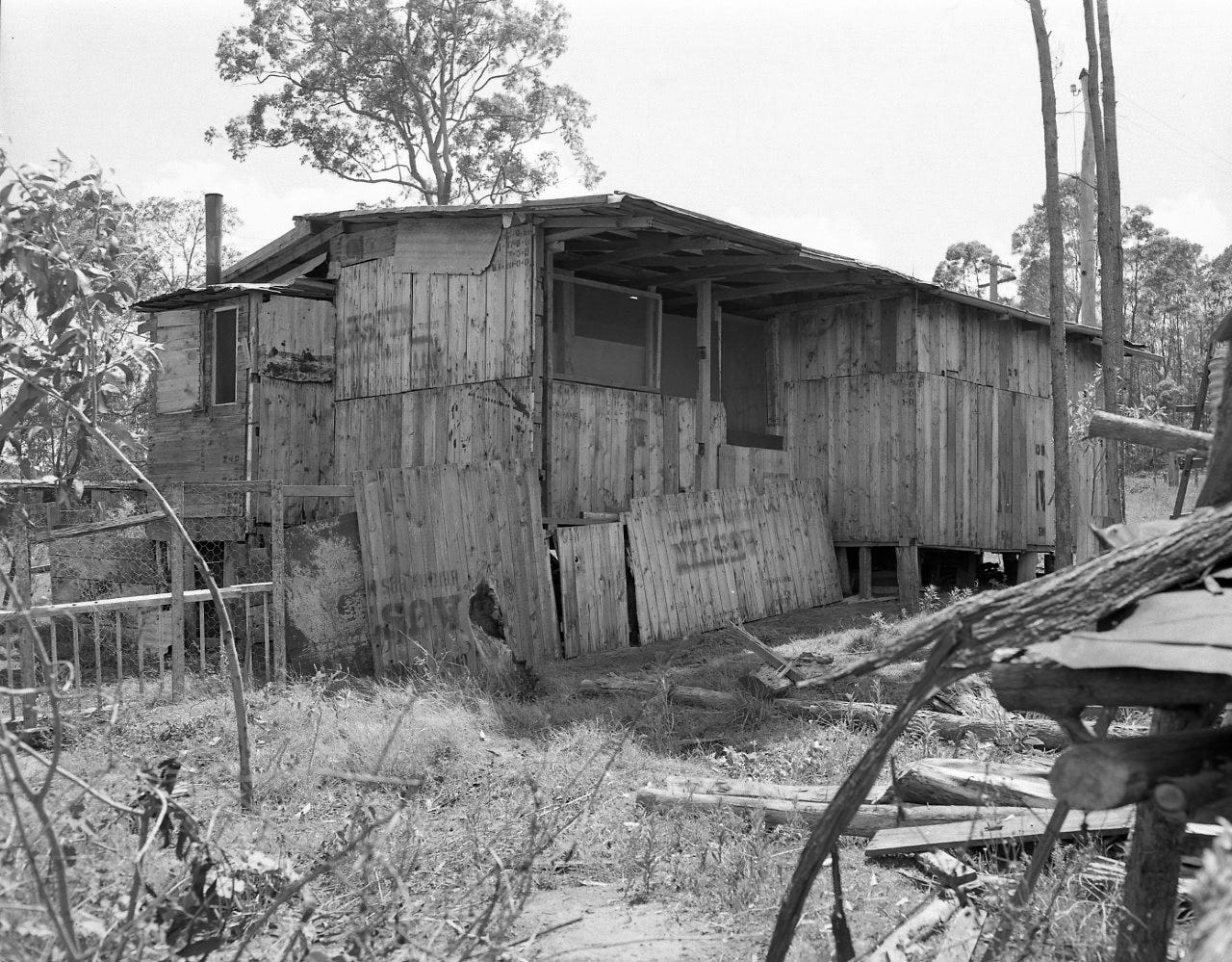

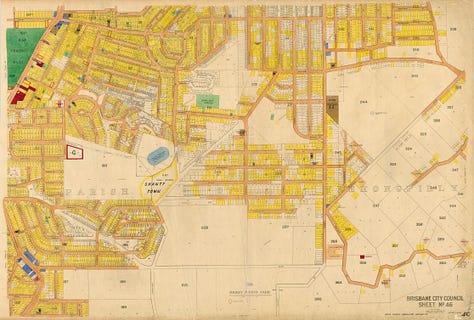

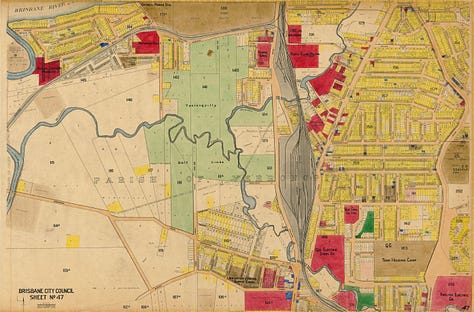

From as early as the 1920s people began to make makeshift shelters on land across cities like Brisbane. A shanty town is marked on this 1951 civic survey undertaken by Brisbane City Council.

This particular camp in Tarragindi overlapped land within the Brisbane City Council reserve as well as private land, at the time owned by prominent doctor James O'Neill Mayne (who left his entire estate to the University of Queensland when he died in 1939).

Tarragindi is one of Brisbane’s middle ring suburbs, about 7 kilometres south of the central city. In 1951, however, it was on the urban fringe. It bordered on Brisbane’s proposed green belt, with most residential subdivisions occurring in the post-war period.

At one point over 500 huts - described as "rude humpies, built of bush timber, and eked out with flattened kerosene tins or other scraps of metal." - dotted Tarragindi's hills and gullies. Homes had been constructed of canvas bags, tarps "or anything which will keep out the rain." Some kept small vegetable gardens.

When a Brisbane City Council inspector visited the camp in 1928, he remarked that some of the residents had been there for five years.

From single men to families

In the 1920s, most residents were described as being older pensioners, and mostly men. By 1928, however, the deepening of the crisis was emerging - with newspapers describing "more coming every day."

By 1946, the site also contained over a dozen families. After World War Two the camp spread to the former US Staging Camp near Mayfield Road at Moorooka.

Brisbane City Council would provide nine sanitary buildings, largely due to complaints about water supply "fouled by the improper disposal of human excrement." A number of "earth closets" (Google tells me these are pit toilets) were supplied by Council.

The Courier Mail stated that 5000 children were living in temporary camps in 1949. The paper stated that the Housing Commission "cannot be blamed for the camps' existence" but "the futures of 5000 children depend on a speedy solution."

Despite a 1950 council attempt to clear the camp, it would remain occupied until 1955.

Lessons for the contemporary crisis?

During the post-war housing crisis the government blamed immigration, unscrupulous landlords and the Great Depression causing shortages of labour and materials (sound familiar?).

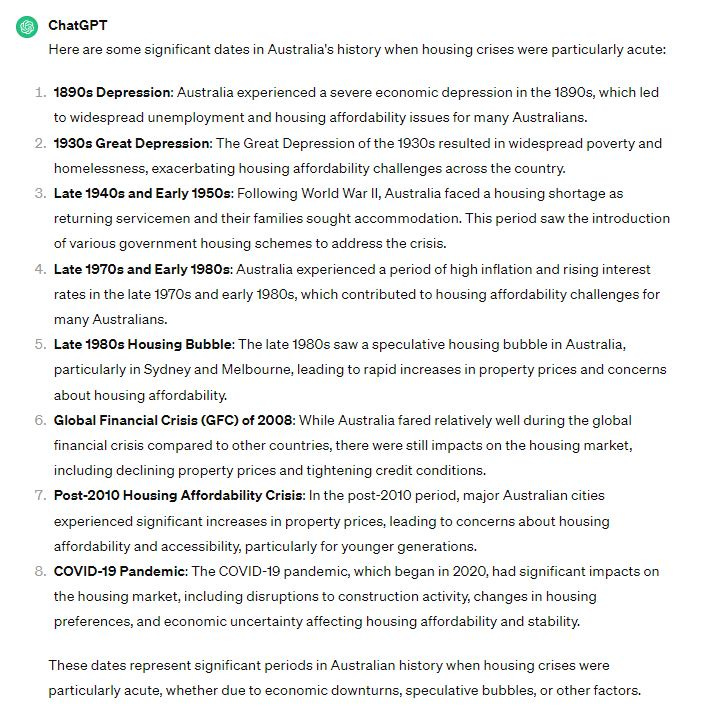

Australia’s history is riddled with housing crises. Can we even call it a crisis when it happens every decade or so?

The institutional arrangements of the post-WW2 period are unlikely to ever be repeated, but the crisis contributed to housing being a cornerstone of the Federal Government's policy agenda.

The 1940s have been described as a "highpoint" for inclusionary housing policy, where

This view was lost somewhere in the midst of the 1980s and 1990s reforms. Reframing housing as a fundamental right (in the same way we view other social infrastructure like healthcare and education) surely provides lessons for the contemporary crisis.

Images sourced from the Brisbane City Council and Queensland Government Archives.